In July 1963, there were riots in Savannah, Georgia. A large headline in the Savannah Morning News read, “Rioting Negroes Stone Cars, Set Fires, Smash Windows.” Several stories were run under the headline about property damage during night marches that turned violent.

I wasn’t born yet, but I know that those front-page stories caused problems for my father, the executive editor of the newspaper. Decades later, he told me his publisher had called him on the carpet over it, saying, “Dammit, Schulte, why did you have to put that on the front page?”

Dad was defensive. “There were five thousand people marching in Savannah last night, and you don’t want me to publish the story? This is big news!”

The publisher continued fussing about the articles. “Next time, bury that in the back of the paper.”

The Civil Rights Act was passed a year later, and one would think that would solve the problems. But people are still marching, and the reason is still buried in the back of the paper. Why is that?

Where I’m living, in Brunswick, Georgia, the median income for a family is $28,564, and 25% of families are below the poverty line. The city’s racial makeup is 60% African-American and 36% white.

Contrast that with neighboring St. Simons island, where the racial makeup is 94% white. There, the median income for a family is $73,580. Only 2% of the families are below the poverty line.

When I first arrived in Brunswick, on my sailboat, Flutterby, the folks at the marina gave us a map of the town. They told us to walk a circuitous route from the marina to the Winn-Dixie grocery store, 2 miles away. “Why’s that?” I asked. “Oh, you know…MLK Boulevard runs through that section,” was the reply. It broke my heart to hear her tell cruising sailors, most of them white, not to even go into the black neighborhood.

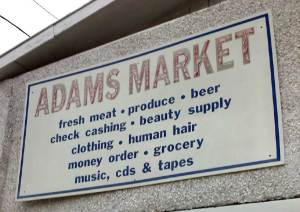

I disregarded her advice, discovering charming houses and intriguing Hispanic grocery stores in that neighborhood. I also discovered a lot of abandoned shacks and lots full of weeds. I had some uncomfortable encounters. This was definitely a neighborhood whose residents struggled to survive.

I returned to the neighborhood this past Monday, on Martin Luther King Day. For the first time, I was marching in the MLK parade with a group of folks from the Unitarian church. The day was beautiful and the mood was buoyant.

At the staging area, I photographed the folks who were in the parade. But as we began marching down Gloucester Street and then turning onto MLK Boulevard, it was the people watching the parade who drew me. I began handing out Happy Spot cards, getting hugs and handshakes, and taking photos of the parade-goers.

Why do I march? I have mixed reasons. I love to celebrate the successes of the African-American community, a group of people whose rich ancestry predates my own on this continent. But I also march as a protest. The law may say otherwise, but inequality persists.

The photos I took that day are full of happy people, but they bring tears of sadness to my eyes. Many of the houses behind the parade-goers are unpainted and unkempt, with bare dirt yards. These are people who live below the poverty line, because they don’t have the wealth of opportunities that I do. The economic figures and demographics are painfully clear. Being black and living in poverty often go hand-in-hand.

During the rest of the year, you won’t see any other parades going down these streets. Until they do, and until we have real equality, I’ll keep marching.

Thank you for marching. I spent a couple of years in the Hilltop part of Columbus and I know exactly what you mean.

Here’s another reason why I still march, from the New York Times (Feb. 10, 2015): Mapping 73 years of lynchings