A half-block from my balcony was a lighthouse, a 75-foot tall structure that dominated my view. I photographed it at all times of the day — at sunrise, highlighted in gold, and sunset, in pink. I spent a lot of time standing on my 4th-floor balcony, gazing at it and the ocean beyond.

The lighthouse was a classic one, broad black and white stripes and a rounded top. It was built on top of a fort that dates back to the 1600s, and the fort was on a grassy park that juts out into the bay.

Just over a week ago, on a Friday night at 10 pm, the grounds were quiet. A couple of people were walking across the lawn under garish green spotlights that made them look bilious. Occasionally, a car or bus drove by.

If this was a park in Vero Beach, or Seattle, the lack of people would be normal. But it was not. I was in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil.

The lack of people last Friday evening was terribly, eerily wrong.

So why was the lighthouse deserted? And why were the streets of the city deserted, as well?

To understand the answer, you have to understand this city with its vast disparity between rich and poor. The police receive salaries that put them closer to poor. Fifteen years ago, they went on strike, and they demanded hazardous duty bonuses. The government agreed, but then broke the promise and never paid them.

So on Thursday, the police went on strike.

When I first heard about it, on a sunny Friday morning, I didn’t understand the implications. I wondered what the striking police officers were doing – were they picketing, or just staying home that day?

With my limited Portuguese, it took me several days to figure out what the striking police officers were doing.

The most visible group of them, together with their families, occupied a legislative building, refusing to leave until their demands were met. Others did random acts of mayhem, like deliberately causing traffic jams.

Overnight, the murder rate doubled. Why? Because there were no police to stop the bad guys? Or – here is the shocking thought — because frustrated policemen become bad guys? In an interview reported by the Associated Press, a representative of the Homicide Department said that at least one third of the murders that occurred during the strike had characteristics of death squads, which include the participation of police and former police officers.

I watched a video on YouTube about an “arrastão,†a word that my dictionary translates as “trawling†or “dragnet.”

A group of rowdy people had just broken into a big store. First, they took the cameras and computers, valuable and small. When those were gone, they took expensive appliances, helping each other carry things like washing machines. Then small pieces of furniture. Eventually, they brought out entire beds, carrying mattresses on their heads.

What kind of people would be desperate enough to steal beds? No self-respecting looter (is that an oxymoron?) in the US would carry a mattress on his head down the street.

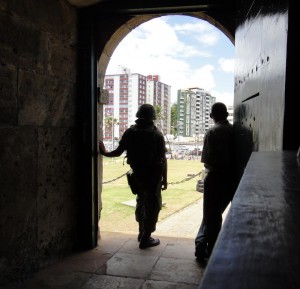

The first night after the strike started was the worst. Thirty reported murders, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Out in the poor neighborhoods, our friends from Salvador say, most murders go unreported. The next day, the Army sent troops, and camouflage-colored trucks full of soldiers drove up and down the main streets. It made people feel a little more secure, but not enough. Ten thousand striking police could not be replaced by only 2000 soldiers.

One was stationed across from my balcony, by the lighthouse. I could see him from my balcony in the wee hours of the morning, a forlorn silhouette with an automatic weapon.

No sleep for the soldier, and no sleep for the people of Salvador. The city was like a tinderbox, ready to go up in flames any minute.

In the poor neighborhoods, people didn’t dare sleep, because there were not enough soldiers to go around. Residents had to stay inside their homes with their doors and windows locked. It was not safe for them to ride the buses, so many didn’t show up for work. In the center of town, businesses were closed and streets normally clogged with traffic had one or two cars on them. Schools postponed opening that week. We went out for ice cream, but the entire shopping mall was closed.

Over all this hung the fear that Carnival, a week away, would be canceled. Millions of dollars would be lost. It was unthinkable.

For a visitor like me, staying in an upscale neighborhood, the peaceful and quiet streets made the strike seem surreal. The only indication of the danger was the US State Department’s warning that Americans should not go to Salvador. But we were already there.

The strike lasted for about ten days, and then, suddenly, it was over. They arrested the leaders and promised the policemen a pay raise later in the year. The police, back on the job, marched in formation down the street, and people cheered for them. The soldiers slouched, relaxed, in the back of their trucks, and made up the other half of the parade. People cheered for them, too. “Propaganda,†said our local friends.

When we got back to our room on Friday night at 9 pm, people were starting to gather at the lighthouse. By 10 pm, the street along the waterfront was completely full, with thousands and thousands of people dancing. The traffic jam on our street stretched for blocks. At 11 pm, a samba band started playing and continued for a couple of hours. At midnight there were fireworks. When the samba band stopped, the noise level continued, with at least four DJs playing amplified pop music.

Were they celebrating the start of Carnival? Or the end of the police strike?

As the party started, I saw dozens of people carrying 30-pound bags of ice on their heads: Beer vendors stocking up their carts. The going rate for beer was 3 for 5 reis, or about a dollar a can. Most people had a beer in hand as they walked down the street. I lost count of the people – men and women – I saw going to the bathroom between the parked cars.

But to my surprise, no one was staggering, or fighting, and I never heard the sound of a bottle breaking. Even the drivers stuck in the traffic jam blew their horns happily, not out of frustration. It was just a big, noisy party. Very noisy. One of the noisiest I’ve ever experienced in my life!

That last night in Brazil, I stood on my balcony, listening to the throbbing sound and people-watching all night long. Sleep was impossible. No sleep for the partying people of Salvador, either. But I think the soldier finally got to sleep. That is, if he was not out partying, too.