When we stopped in the boatyard office to pick up our mail this morning, we mentioned to Carolyn that we were planning to drive to the Cedar Island Wildlife Refuge today. “Oh, you’re going to the end of the world, then,” she said, matter-of-factly.

In preparation for our trip to the end of the world, we packed energy bars, water, and lots of cameras. The gas tank was full, and we had lots of great music on the car stereo.

I spent some time on the internet, looking for information about the wildlife refuge. Although it looked large on the map, I couldn’t find any roads or trails within it. I figured that was an oversight by Google Maps. We are talking end of the world here.

Outside of Beaufort, there’s a sign that makes us laugh. It reads:

Sea Level 27

Atlantic 30

It’s not meant to be facetious. It’s a green highway sign — 27 miles to the town of Sea Level, and 30 miles to the town of Atlantic. Neither one is actually the end of the world, but they’re close.

Cedar Island isn’t actually the end of the world, either. There’s a ferry terminal there, and the boat to Ocracoke is crowded with tourists and residents and even semi trucks. However, the strip mall near the ferry is in a state between fading and crumbling, and all the shops have failed. There’s an old motel, with gaps in the roof where there used to be shingles.

The town of Cedar Island has about 300 residents, and fishing is a major source of income. In one front yard, a husband and wife were repairing green fishing nets, using the same sort of gear we learned about when we sailed to Juneau, Alaska. Down the block, a father and son were stretching their brown nets out in the driveway for repairs.

A few blocks from Goodwin Ridge Road, we drove past the Oscar B. Goodwin Family Cemetery. There are five Goodwin homes on the island over 100 years old. And the Goodwins are still living here, as evidenced by a sign for Goodwin’s Guide Service.

As we drove through town, a dog darted out in the road. He was agitated, and when I stopped, I saw that he was chasing the red pickup truck in front of us. He kept running at top speed for over a quarter mile, barking at the truck. Finally, the truck pulled over and the dog jumped in the back. They were trying to go someplace without him, and the dog just wasn’t going to put up with that!

We finally found the end of the world when we turned toward the refuge office. Trees draped with Spanish moss hung over the road, and there were a few small houses and a single-wide mobile home with a front yard full of 19th-century tombstones.

A couple of miles down Lola Road, I slowed to a crawl, trying to figure out a strange sight. It was a riding mower in the left lane, with a rounded plaid object sticking out of it. It took me a second to realize the plaid object was a man’s derriere. He was repairing the mower right there in the road.

At the end of the road, we found an information kiosk with a map, but like Google Maps, it showed no roads into the refuge. We decided to go into the nondescript cinder block building and ask.

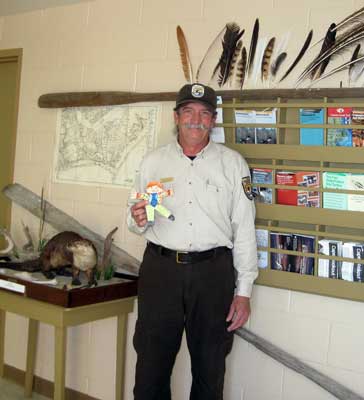

This is where we met the man who works at the end of the world. Kevin Keeler, a tall man with a gray ponytail and an easy laugh, had a long career with the Department of Defense, at one point supervising about 50 people. But they cut back on staff before he was ready to retire, so seven years ago, he took his current job with the Department of the Interior.

Now Keeler works alone. Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge has a staff of one, and he is it. He manages 14,400 acres, doing everything from paperwork to mowing to “cleaning the shitter,” as he puts it. His title, a complete understatement, is “Maintenance Worker!”

The end of the world has an interesting history. In 1964, the federal government acquired the land for the refuge. There was a town then, called Lola, adjacent to the refuge. In 1967, in a reaction to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Navy used the right of eminent domain to take the 16 homes that made up Lola. They demolished the houses and put up a radar dish that could see south and east, just out of range of the Cuban missiles of the day.

Within three years, the Navy no longer needed the once-critical facility. By then, we’d put a man on the moon, and they were probably getting better information from satellites than the archaic land-based radar. They transferred the facility to the Department of the Interior — the Wildlife Refuge. Which is why local folks sometimes say, “The wildlife refuge took my granddaddy’s land.” Not precisely.

For about 19 years, there was a man in charge of the refuge. Then they consolidated the various refuges as a cost-saving measure. For Cedar Island Wildlife Refuge, that meant closing the office and leaving the place to fend for itself for 15 years. After all, it was a wildlife refuge, not a people refuge.

When they hired Keeler in 2003, he found the building covered in vines and filled with several feet of silt. Across the street, one of the Navy buildings had to be demolished as a safety hazard. Worst of all, the refuge had become a dumping site. He described the trash he found: “Washers, dryers, construction equipment, cars…and the tires!”

A local Outward Bound group helped clean up the tires. “You know how many we found, just between here and the highway?” Keeler asked. “Two hundred and eighty-seven, and eighty-five of them were still on the rims!”

In addition to giving us the history, Keeler showed us how to get into the refuge. We parked on the highway and walked along one of the fire breaks, marked on the map as “unimproved trails.” We had the place to ourselves, and the only sound accompanying our footsteps was the wind sighing in the trees.

On this warm, sunny day, the end of the world was a very good place to be.

Later, we found out we’d been incredibly lucky. The real reason nobody goes into the wildlife refuge, besides a lack of trails and roads and facilities and promotion? Mosquitoes!

According to Carolyn, Cedar Island is the worst place in the area for mosquitoes. “There are so many, they’ll carry you away,” she said. Yet we didn’t see a single one. We just happened to go during that tiny window between winter and spring, when the mosquitoes hadn’t hatched yet.

I’ll worry a little bit about Keeler, though. There he is, at the end of the world, but he’s not alone. He’s surrounded by hordes of giant blood-thirsty mosquitoes, and one of these days, they just might carry him away.

In my Santa hat? There’s a tradition! We wear our Santa hats all the time in December. When it’s warm, don’t come on the boat — we might not be wearing anything with them. When it’s cold, my Santa hat goes great with my pink Death Bunny pajama pants. Which I sometimes wear out in the boatyard, just for grins.

In my Santa hat? There’s a tradition! We wear our Santa hats all the time in December. When it’s warm, don’t come on the boat — we might not be wearing anything with them. When it’s cold, my Santa hat goes great with my pink Death Bunny pajama pants. Which I sometimes wear out in the boatyard, just for grins.