After looking at the boat in Portimão, we were full of unanswered questions. Rather than trying to force a decision, we elected to be tourists for a few days and let the questions roll around in our subconscious minds.

We were definitely not going to spend a second night in Portimão. It wasn’t as much of a dump as we’d expected, but there wasn’t much to see in the wintertime. At 20 Euros, the lodgings we’d found were cheap, but we got what we paid for: A sleepless night with no heat on two very lumpy twin beds. We were ready to move on.

We bought a couple of bus tickets to Évora and boarded a local bus to Albufeira, where we would transfer. I fought down my usual nervous what-if fears — what if we couldn’t figure out which bus to get on? What if we missed our transfer? What if we couldn’t find a place to stay?

But the first leg went smoothly, with the bus following the coastline of the Algarve and giving us lovely views of the blue Atlantic between clusters of high-rise condos and billboards in English.

Like our Florida, retirees from the chilly north — England and Germany, especially — have flocked to this region. The old buildings are bulldozed and replaced with high-rises, and there are more billboards in English than Portuguese. A few unspoiled villages remain, but they are at risk of being overrun as well. The money is much-needed, but the loss of the fishing villages and the old ways is sad, and lamented by many of the younger Portuguese people we met.

It’s probably lamented by the older Portuguese people, too, but fewer of them spoke English. So we were unable to lament with them.

On the bus to Évora, we met an exception, a middle-aged woman in the seat behind us who napped for the first hour of the trip. When she awoke, she was as friendly — and as persistent — as a puppy. “I love to speak English!” she told us. We soon realized that although she had lived in Évora her whole life, she was not a typical resident.

She told us that she loved the USA and visited there several times a year for “conferences.” She expanded on this, until we figured out that she was involved in a multi-level marketing scheme that she expected to provide a comfortable retirement when the Portuguese social security system collapsed. She was cheerfully insistent that although she never had to sell anything, she would be able to raise tremendous sums of money while “helping people.”

Over the course of the conversation, which gave me a crick in my neck from turning backwards, our seat neighbor told us her home was inside the medieval walls and had 37 rooms. She’d left her husband and mother at their beach house and was only coming up for one day to sign some papers. Although the 120-mile bus ride took almost four hours, she preferred it to driving, because it was much cheaper.

She was so garrulous that we soon learned about her husband’s health issues and the fact that he was now a vegetarian Buddhist. She had recently converted to Mormonism herself. I imagined that between their weird diets (how does she get along in a country where coffee or wine is served with every meal?) and the multi-level marketing scheme, they probably didn’t get a lot of dinner invitations from friends.

When we arrived at the Évora bus station, it was dark, we had no place to stay, and we were hungry. Our plans to read the guidebook had been foiled by our talkative neighbor. Luckily, she’d recommended a place to stay, so we were able to drop our bags and immediately go out exploring. We had no idea what we would find.

For dinner, we discovered a tiny jewel of a restaurant, where local folks sat laughing around tables with ceramic pitchers of local Alentejo wine. The vaulted ceiling hinted at the building’s origin as a cloister. We stuffed ourselves with migas, a breadcrumb dish with asparagus and cheese, and bacalhão, the ubiquitous — and tasty — salt cod. The place was so small, Barry was practically sitting in the dessert cooler. He salivated throughout the meal, so we had to order desserts, too. Chocolate mousse, bread pudding, cake made with corn flour — it was so hard to choose!

Leaving the restaurant, we began wandering the dark, narrow cobblestone streets with our camera in hand, flattening ourselves against the wall when a car careened through. We came around a corner and discovered the 13-century cathedral, dramatically lit with spotlights. I stood staring up at the portal in awe. In college, I’d once spent three months studying this sort of thing — three months of portals. I’d seen hundreds of photographs, and finally, I was seeing the real thing. I couldn’t believe I was here, seeing it, and that we had it to ourselves. Not a tourist in sight.

[Photo: Left jamb of the main portal, Évora cathedral]

Barry set up our tiny tripod and was shooting photos when something caught my eye up the street. Whatever it was, it had spotlights on it, too.

“Come this way!” I said. I thought maybe it was another church.

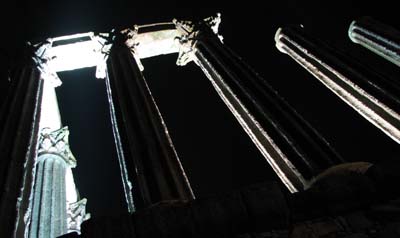

Instead, we rounded another corner and found the ruins of a Roman temple from the first century. From a distance, the fourteen Corinthian columns looked perfect and symmetrical. Up close, the stones were pitted and weathered by a couple of thousand years. The columns were bigger than I’d ever imagined, towering 40 feet over our heads.

It was magical. And we had it to ourselves.

[Photo: Roman temple, Évora]

Évora is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, something that probably attracts lots of tourists. In the summer, that is. We did see a few of them when we returned to the cathedral and temple the next day. We saw the same tourists a few blocks away at the Capella dos Ossos, the Chapel of the Bones, where the walls and ceiling are lined with the bones of thousands of monks.

But when we went out on our nighttime photography expeditions, the tourists were absent. When we explored the local cemetery, there were no tourists. When we took our bread and cheese to the park for a picnic, we shared the place with a few birds and one butterfly.

[Photo: Mausoleums, Évora cemetery]

And when Barry found a crumbling medieval tower at dusk and dragged me to the top, we were completely alone. The staircase was grown over with brambles and weeds, as if no one had been up there in years. I was terrified, certain that I’d fall off the edge or the staircase would collapse under me.

Évora is a small town made up of layer upon layer of history, something I’d not experienced in North America. Standing alone in the medieval cathedral, I pictured the builders preparing the site in the thirteenth century. Craning my neck at the Roman ruins, I imagined the centuries of people who walked by this edifice every day of their lives, so used to it that they paid it no attention.

I paid it plenty of attention. For two magical days and nights, I passed it often. Every time, it transported me to another world, where my imagination could run free.